One of the shortcomings of the fallout shelter program of the 1950’s- 1970’s was the lack of communications from shelters to the outside world. The 1962 Fallout Shelter Plan for St. Paul, MN, for example, stated that “many designated shelters will be in places with access to existing telephones. When telephones are available and operable they will serve as basic communications.” The plan also stated, but apparently with no thought as to who would be responsible, “plans should be made to insure that at least one battery operated AM radio receiver plus extra batteries will be made available in the shelter for reception of emergency broadcasting information.”

When I was a student in elementary school, I noticed these gaps. One year, during a tornado drill (that had been scheduled well in advance), I was quite pleased to see that one of the teachers had with him down in the basement a battery-operated radio. It was rather reassuring to see it, since I knew we wouldn’t be cut off totally from the outside world in the event of an emergency, since we would still be able to receive whatever emergency instructions might be forthcoming from the radio.

My reassurnce was dashed that afternoon, however, when I saw that same teacher walking home, carrying his portable radio. It was apparently his personal radio, which he brought to school in preparation for the scheduled drill. In other words, it wouldn’t be around in the event of an actual emergency. If the power were out, we would, indeed, be cut off from the rest of the world.

On another occasion, the school administration was going to have an additional twist on the drill. Instead of heading to the designated shelter when the school’s own bells sounded the warning, each class was instead going to act when the sirens outside went off. When we heard the siren, we were to head for the basement.

Unfortunately, the closest siren was miles away, and wasn’t very loud where we were. Undaunted, my classroom teacher had a solution to the problem. Shortly before the scheduled test, she opened a window at the back of the room, and a designated student sitting near that window was tasked with listening for the siren. The plan went off without a hitch. He heard the siren and warned the class, and we all headed for the shelter. Of course, it occurred to me that the window wasn’t normally left open. In an actual emergency, nobody would have heard the siren.

The 1962 St. Paul shelter plan realized many of these shortcomings, and stated that “two-way radio is being considered as back-up to telephone communication.” It also considered the possibility of using amateur radio. Under the heading of “other desirable equipment” was “portable transmitting-receiving equipment belonging to members of units of RACES (Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Service). Plans will be made to have designated ‘hams’ take their portable equipment to shelters upon receipt of warning.”

I’m not aware of any specific plans worked out to use RACES in fallout shelters. However, on the national level, there was indeed some planning taking place for two-way radio equipment in shelters. Even though some planning was done, as far as I’m aware, this was never put into place.

In a 1962 report entitled “Fallout Shelter Communications Study,” the engineers conducting this study used Montgomery County, Maryland, as an example, and determined what kinds of communication would be appropriate between the fallout shelters and Emergency Operating Center (EOC) in what the study considered to be a fairly typical county. The report concluded that the telephone system should serve as the primary communications network for these needs, but also recognized the desirability of two-way radio, and came up with a budget of $391,000 for the county. Each shelter’s radio was budgeted at a minimum of $250, with another $50 set aside for the antenna.

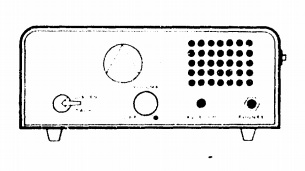

Specifications for equipment were contained in a 1964 report prepared for the Office of Civil Defense by the same engineering firm. The sketch here of a prototype transceiver for shelter use is from that report. This report provided specifications for the equipment in each shelter. The radio for use in the shelters is shown here, and could be either VHF or UHF, in the 150, 460, or 950 MHz band.

Specifications for equipment were contained in a 1964 report prepared for the Office of Civil Defense by the same engineering firm. The sketch here of a prototype transceiver for shelter use is from that report. This report provided specifications for the equipment in each shelter. The radio for use in the shelters is shown here, and could be either VHF or UHF, in the 150, 460, or 950 MHz band.

A key concern in the design specifications was the fact that the radios would be left unattended for long periods of time. Therefore, non-corrosive properties were important, and ferrous metals were to be avoided to the extent possible.

Power supply could be either 120 volts AC, or 12 volts DC. The problems of storing batteries for long periods of time was a challenge, and consideration was given to storing dry batteries. In addition, batteries from vehicles could be used. Presumably, they would be brought into the shelter in an emergency. If the battery needed replacing, presumably a short excursion out to the parking lot could be made when radiation levels decreased.

Ease of operation by untrained personnel was also a concern. The unit did not have an external microphone. Instead, both the microphone and speaker were built in, with a push-to-talk switch on the panel. The only other control on the panel would be the volume control and power switch. The unit was to have a squelch control, which would be accessible from the front panel. However, it would be preset, requiring a screwdriver to make any adjustments. It did include a headphone jack for private listening.

The cost for equipment was estimated at between $250 and $420 per shelter, with an additional $10 to $100 for the antenna, which would be installed prior to the emergency.

It was recommended that the radios be licensed as local government service, perhaps on the same frequencies as other municipal services. It was anticipated that any necessary drills might be conducted on weekends, causing minimal interference to the other governmental users.

Visit my website for more free emergency preparedness and civil defense materials