I suspect that most who are familiar with the “foxhole radio” learned about it from the 1950’s era book All About Radio and Television by Jack Gould

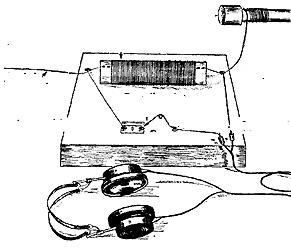

I suspect that most who are familiar with the “foxhole radio” learned about it from the 1950’s era book All About Radio and Television by Jack Gould. This book, a staple of many elementary school libraries, includes the crystal set shown here, which was constructed using a razor blade and pencil lead as the detector. Gould recounts how such a radio was used by soldiers in the fox holes of World War 2, and I suspect that it was the appearance in Gould’s book that popularized the name. And it turns out that Gould probably originated the name.

The name “foxhole radio”, and perhaps the concept, seems to have originated from the construction of simple crystal sets by soldiers at Anzio in 1944. From March through early May, 1944, fighting was light, “living was leisurely” for the thousands of soldiers on the beachhead, and the beachhead was a “honeycomb of wet and muddy trenches, foxholes, and dugouts.”

One of the first references to the fox hole radio I’ve been able to find appeared in QST for July, 1944. It doesn’t use the term “foxhole radio,” but this “Stray” reads as follows:

According to Toivo Kujanpaa, a licensed ham op stationed on the Anzio Beachhead, several of the radio men there rigged up a field version of a “crystal” set using a razor blade for a detector. Their efforts were rewarded by the reception of a “jive” program (along with some German propaganda) aimed at the American forces from an Axis station in Rome.

About that same time was when, as far as I can tell, a variation of the name “foxhole radio” first appeared in print. Time Magazine for July 17, 1944 made the report,. Time reported that one Lt. M.L. Rupert was one of “hundreds of U.S. infantrymen” who made the foxhole receiver to kill time and boredom at Anzio. Lt. Rupert wrote to Marlin Firearms Company (the manufacturer of the razor blades) with a description of the set.As QST later lamented, Time “as usual” hadn’t given credit to hams for coming up with the idea.

A similar account, also crediting Lt. Rupert’s letter to the manufacturer, appeared in the New York Times on June 25, 1944. According to the New York Times, the idea of using the pencil lead originated with O.B. Hanson, NBC’s vice president of engineering, who refined on the concept sent to the razor blade manufacturer. Interestingly, the byline of the New York Times account is none other than Jack Gould, the author of All About Radio and Television. So it’s safe to say that Gould is the originator of the name “foxhole radio.”

There were two follow-ups in QST. The August issue contains the following Stray:

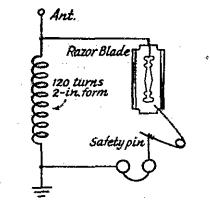

Further details on the foxhole radio sets now have been received from a correspondent in Italy. The razor blade and safety-pin detector is described as follows: “A station was found by moving the point of the safety pin, anchored at the other end, over the opposite end of the blade from where it is connected to the coil and antenna. The ‘phones are inserted between the pin and the grounded side of the coil.” He adds that “reception was very good.”

Finally, a letter appears in the October issue of QST from Justin Garton. No call sign is listed, but Garton’s address is shown as 448 Riverside Dr., New York, N.Y. Garton reports that the boys on the Anzio beachhead were able to receive Rome during the day and Nazi propaganda programs from Berlin at night. Garton also includes the following schematic:

I wasn’t able to find a call sign for either Kujanpaa or Garton. Since the Stray indicates that Kujanpaa was licensed but didn’t give his call, I’m guessing what happened was that he was licensed after Pearl Harbor and consequently did not receive a call sign. It’s possible that he received a call after the War, but I wasn’t able to find it. According to this enlistment record, one Toivo J. Kujanpaa of Massachusetts, born in 1910, enlisted on June 11, 1943. According to the Social Security Death Index, he was born on June 19, 1910, and died on January 6, 1991. Its quite likely that he got his amateur operator license after Pearl Harbor but before enlisting a year and a half later. With the wartime moratorium on station licenses, he would not have received a call sign, despite being licensed.

If you’re an ARRL member and logged into your account there, you can download the QST articles cited above at the following links:

- Radio Men Rigged Up a Field Version of a Crystal Set, July 1944

- Foxhole Radio Sets, August 1944

- Foxhole Radio (Correspondence), Oct. 1944

And this June 1945 Stray submitted by W2MIB includes an alternative detector,

Update: Gould’s book “All About Radio and Television” is now available for free download at AmericanRadioHistory.com.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon ![]()

Pingback: Foxhole Radio Update | OneTubeRadio.com

I loved that book! My dad took me to the local electronics store and had them wrap about 100 turns of copper wire on a cardboard roll. I carefully assembled all the components (razor blade, safety pin, pencil lead, earphones) as directed and grounded it on our water pipe outside. I couldn’t believe it worked!

The tuning was a little haphazard, but I was able to listen to several stations right off the bat. I was eleven or twelve at the time, and thought that the foxhole radio was the greatest thing since sliced bread.

The artist who did the cover was apparently a little unclear on the concept.

As shown in the diagram above, the ground wire is attached to a water pipe. But the helpful dad took the diagram a little bit too literally and broke off the pipe before winding the wire around it.