Most people who buy inexpensive radios like the BaoFeng UV-5R are doing so to communicate through repeaters. A repeater is a station, usually located at a high location, which picks up weak signals and retransmits them over a much larger area. Therefore, with even a cheap radio, it’s trivially simple to communicate tens or even hundreds of miles. And if the repeater is linked to other repeaters with a system such as Echolink, then it’s possible to communicate worldwide.

are doing so to communicate through repeaters. A repeater is a station, usually located at a high location, which picks up weak signals and retransmits them over a much larger area. Therefore, with even a cheap radio, it’s trivially simple to communicate tens or even hundreds of miles. And if the repeater is linked to other repeaters with a system such as Echolink, then it’s possible to communicate worldwide.

Of course, it’s also quite simple to communicate worldwide with your cell phone. In both cases, you’re relying upon equipment supplied by someone else. In the case of the cell phone, you can call Japan because you’re paying your local cellular provider, and they provide the infrastructure to route your call to the phone company in Japan. In the case of amateur radio, you are relying upon the owner of the repeater, and the volunteers who link it up into networks such as Echolink. It can be interesting chatting with someone around the world with your $30 radio, but there’s nothing particularly remarkable about it.

It’s more remarkable to know what your radio is capable of, relying on nothing other than your own station, the laws of physics, and the equipment owned by the one person with whom you want to talk. This is why, in my opinion, HF (high frequency, the part of the radio spectrum below 30 MHz) is a lot more interesting than VHF. On HF, it is indeed possible to send radio signals around the world using simple equipment, and not relying on anyone other than myself and the station I’m talking to.

If you have only a $30 VHF radio, I encourage you to try out things like repeaters and Echolink, because they can be fun parts of the hobby. But eventually, if you have any curiosity, you’ll want to know what your radio is capable of. What is it capable of doing without all of that equipment supplied by other people. You may want to do this because it’s an enjoyable hobby. People enjoy fishing as a hobby, even though you can buy fish at the supermarket. And many people enjoy communicating by radio, even though you can buy the same services from your friendly cell phone provider.

Some people are interested in knowing the capabilities of radio communications because they are concerned about emergencies in which the friendly local cell phone provider might be unable to provide those services. In any event, it can be helpful to know what the radio can do by itself.

This is why I decided to try it out in this weekend’s VHF contest. Many hams who engage in “contesting” take the activity very seriously. They spend countless hours and hundreds or thousands of dollars making the best possible station. They can routinely make contacts of hundreds of miles using the same frequencies used by your cheap handheld. Barring very unusual conditions, you will not be able to communicate hundreds of miles directly with your handheld. But you can experience some of the same magic.

I did learn that there’s a reason why some hams spend thousands of dollars. The thousand dollar stations actually work better than the $30 stations! It turns out the Achiles Heel of this radio is the receiver’s wide front end.

In fact, it turns out that there’s really no sense in using an external antenna with this radio, at least in a metropolitan area, since strong signals in the area are going to render the receiver unusable.

Hams have a saying that “if you can’t hear ’em, you can’t work ’em,” and this radio proves the truth of that adage. I can confirm that this $30 radio is able to get out over 40 miles on simplex, because I was heard by a station that far away. But despite his having a much better station than mine, I was unable to hear him.

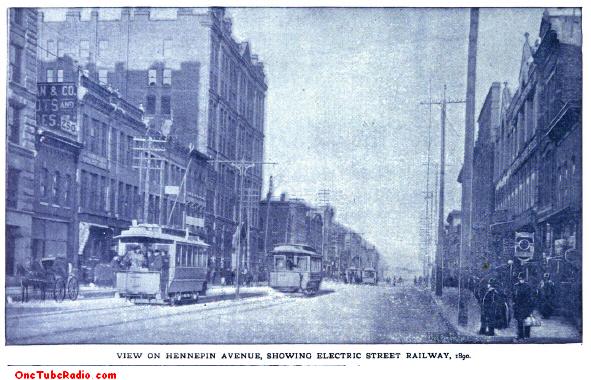

I hooked the radio up to my outside vertical and put out some CQ’s. I later learned that one of the stations coming back to me was in Red Wing, Minnesota, which is about 41 miles away. He was copying my five watts just fine, but I never heard him when he came back to me. I didn’t even know he was there, until another station about a mile away told me that he was calling. I switched over to the Kenwood mobile rig in my shack, and I was able to work him with no difficulty. In fact, he had a very strong signal, due to the fact that he has a good beam antenna mounted up high.

This illustrates something that might be counter-intuitive to a lot of newbies: It’s quite easy to make a good radio transmitter, but it’s hard to make a good receiver. Almost invariably, the difference between a cheap transceiver and a good transceiver will be that the good one has a better receiver. There’s very little that one can do to make a transmitter work any better. Either it’s radiating RF or it’s not. There’s very little that you can do to make it more effective. When I worked the other station on my other rig, it really didn’t make much difference that I was using 25 watts instead of 5. I doubt if he was able to copy me any better. In fact, he probably didn’t even notice the difference.

The big difference was that I wasn’t able to copy his fairly strong signal. So the quality of the receiver makes a huge difference.

It’s not too surprising that the Baofeng’s receiver received so poorly. It covers a very wide range of frequencies. On VHF, it covers 136-175 MHz. It has very little filtering in the front end, and the filter is designed to let any frequency within that range through. And within that frequency range, there are a huge number of transmitters within the area. The receiver has to deal with those signals, and through a process called “desensing”, it deals with them by reducing the sensitivity to every other signal, including the one I want to listen to.

This isn’t really a defect in the Baofeng’s design. After all, it is a handheld radio, and it’s supplied with and designed to operate with an inefficient antenna. In normal operation, it’s not going to put out a very strong signal, because it’s only five watts going to an inefficient antenna. It’s a very reasonable assumption that the station on the other end is going to be more powerful, such as the output of a repeater.

Also, the receiver is relatively sensitive to start with, as long as it’s not overloaded with other strong signals. And when it’s used as intended–with the built-in antenna–those other signals aren’t particularly strong. That means that when it’s used with a cheap antenna, the receiver actually performs about as well as a good receiver would, if that other receiver were also used with a cheap antenna.

I’m able to see this from the weather stations that I’m able to receive with the stock antenna. My other VHF handheld, a Yaesu VX-3R , is able to receive only one weather signal, the strongest local one on 162.55. The Baofeng, on the other hand, is able to receive three of them from some distance, as long as it’s using the cheap antenna. But when I hook the Baofeng to an external antenna, those weaker stations disappear. They are still there, and in fact they are much stronger now. But all of the other stations in the area on 136-175 MHz are also much stronger. And the combined effect of all of those other stations is that they completely prevent reception of the weaker signals.

, is able to receive only one weather signal, the strongest local one on 162.55. The Baofeng, on the other hand, is able to receive three of them from some distance, as long as it’s using the cheap antenna. But when I hook the Baofeng to an external antenna, those weaker stations disappear. They are still there, and in fact they are much stronger now. But all of the other stations in the area on 136-175 MHz are also much stronger. And the combined effect of all of those other stations is that they completely prevent reception of the weaker signals.

It boils down to the fact that the adapter for the external antenna isn’t particularly useful. The receiver actually works better with the inefficient “rubber duck” antenna. There would be very few situations where the external antenna would improve reception.

There might be a handful of situations where an external antenna could be helpful. For example, if you’re using the radio in a rural area with very few transmitters nearby, the advantage of an outdoor antenna might outweigh the desensing effect. But in general, this radio is probably most useful with the cheap antenna that was supplied with it. The situations where an external antenna would be an advantage are probably pretty rare.

I started this experiment to determine whether or not a $30 radio would be useful for contesting. And lo and behold, the shocking conclusion is that spending hundreds or thousands of dollars on gear will probably do a better job than trying to get by with a $30 radio.

But as long as you understand the limitations, you can have some fun with a $30 radio in a VHF contest. My best DX seems to be about 10 miles. Again, I was getting out much further than that, but it wasn’t possible to make a 2-way QSO. I made some of those 10 mile QSO’s with the mobile antenna on the car. But it turns out that I also made some of them with just the rubber duck antenna. And I probably would have made more if I hadn’t worried about the external antenna. If you live in a mountainous area, you’ll probably do much better than 10 miles by “hilltopping”–bringing the radio with you to a very high location away from other sources of VHF radio signals.

If you do have one of these radios, I encourage you to try it out during the next VHF contest. Some of the popular upcoming contests that could be worked with a radio like the Baofeng are:

During any of these contests, if you get on the air (the frequencies 146.55 MHz and 446.000 MHz would probably be the best starting points) and call “CQ Contest” from a high location, you’ll probably make at least a few interesting contacts, and realize that even a cheap radio is capable of producing some fun contacts over a longer distance than you would have expected.

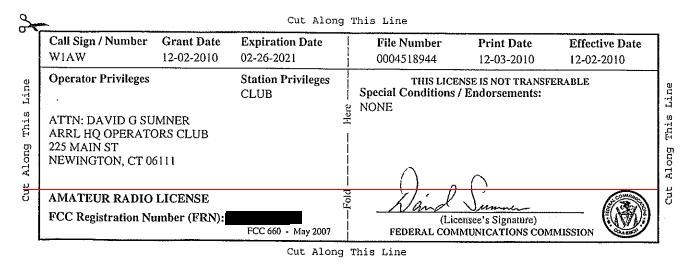

Many areas have a radio club that will promote activity and provide guidance to new hams wanting to try out contesting. You can find a list of local ham clubs on the ARRL website.

In Minnesota, the club that is focused on VHF contesting is the Northern Lights Radio Society. If you’re located in Minnesota or the surrounding states, it’s a good idea to check in with them before the contest for some pointers and encouragement. Even if you can’t find a local club, it’s worthwhile getting on the air during a contest to see if anyone’s around. You’ll probably make a few contacts, learn the capabilities of your radio, and have some fun in the process.

For more information:

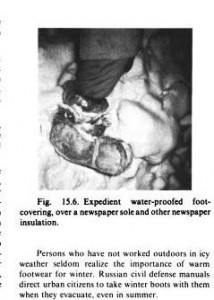

If the snow is wet, place a piece of strong plastic film or coated fabric outside the insulating layer, after securing it with the first strip of cloth. The outer protective covering should be tied over the waterproofing, with the second strip of cloth securing both it and the waterproofing. (When resting or sleeping in a dry place, remove any moistureproof layer in the foot coverings, to let your feet dry.) Figure 15.6 shows a test subject’s waterproofed expedient footcovering, held in place as described above, after a 2-mile hike in wet snow. His feet were warm, and he had not stopped to tighten or adjust the cloth strips.

If the snow is wet, place a piece of strong plastic film or coated fabric outside the insulating layer, after securing it with the first strip of cloth. The outer protective covering should be tied over the waterproofing, with the second strip of cloth securing both it and the waterproofing. (When resting or sleeping in a dry place, remove any moistureproof layer in the foot coverings, to let your feet dry.) Figure 15.6 shows a test subject’s waterproofed expedient footcovering, held in place as described above, after a 2-mile hike in wet snow. His feet were warm, and he had not stopped to tighten or adjust the cloth strips.

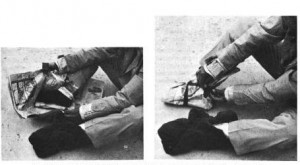

made of corrugated cardboard, and used only about three sheets of newspaper. I then tied these as indicated in Kearney’s instructions. I finished by covering them with a plastic grocery bag.

made of corrugated cardboard, and used only about three sheets of newspaper. I then tied these as indicated in Kearney’s instructions. I finished by covering them with a plastic grocery bag.