x

x

Amateur Radio signals first crossed the Atlantic 100 years ago the night of December 11/12, as documented here in the December 12, 1921, issue of the New York Herald.

Amateur Radio signals first crossed the Atlantic 100 years ago the night of December 11/12, as documented here in the December 12, 1921, issue of the New York Herald.

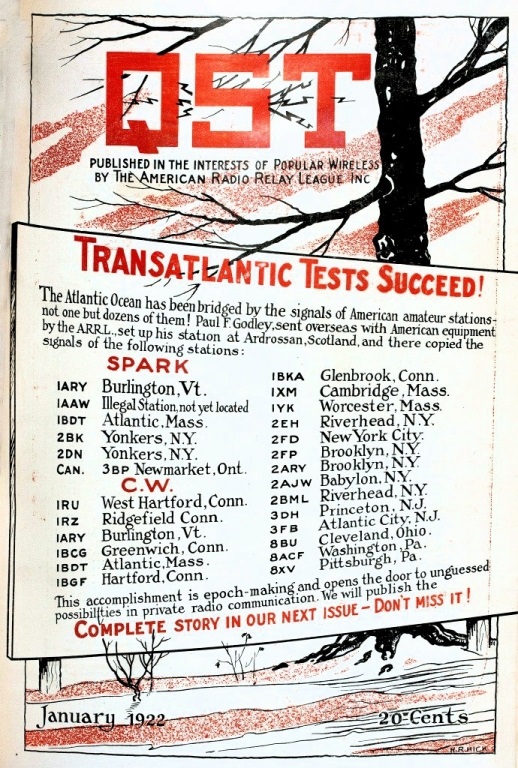

An attempt the year before had been unsuccessful, and in 1921, the American Radio Relay League pulled out all the stops to ensure success. In addition to European operators who would be listening in, American Paul Forman Godley, 2ZE, was sent to England with the latest in American receiving equipment. He set up in a field at Ardrossan, Scotland, with only a tent to house himself and the receiver.

Transmissions from North America followed a pattern. Between 7:00 and 9:30 PM Eastern Time, all stations were invited to send, with a 15 minute period designated for each call area. These stations simply called TEST and their call sign. Starting at 9:30 until 1:00 AM, about two dozen pre-selected stations took turns calling. Each of these stations sent a five-letter cipher which had been given to them in a sealed envelope.

My personal connection to the tests is the fact that one of these stations, 9XI at the University of Minnesota is one I personally operated many times, and of which I served as trustee for several years. In those early years, there was a fuzzy line between amateur stations and broadcast stations. At some point there was a split, and the broadcast side of 9XI became licensed as WLB, and later as KUOM, under which call it still operates.

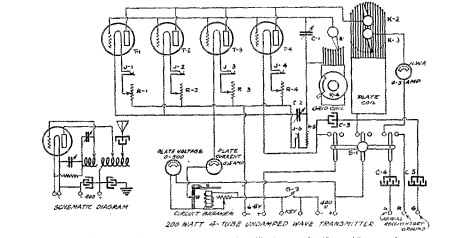

Amateur station 9XI became 9YC, later W9YC, and after the war, W0YC, the call it held when I was a member and later the licensee. With the exception of 6XH at Stanford University in California, 9XI was the furthest west station participating. It was not heard in Europe, but the station sent the cipher SFLJT on 300 meters (1000 kHz) using CW. The transmitter was undoubtedly the one shown at left, described by Prof. Cyril M. Jansky, Jr., in the December 1921 issue of QST.

Amateur station 9XI became 9YC, later W9YC, and after the war, W0YC, the call it held when I was a member and later the licensee. With the exception of 6XH at Stanford University in California, 9XI was the furthest west station participating. It was not heard in Europe, but the station sent the cipher SFLJT on 300 meters (1000 kHz) using CW. The transmitter was undoubtedly the one shown at left, described by Prof. Cyril M. Jansky, Jr., in the December 1921 issue of QST.

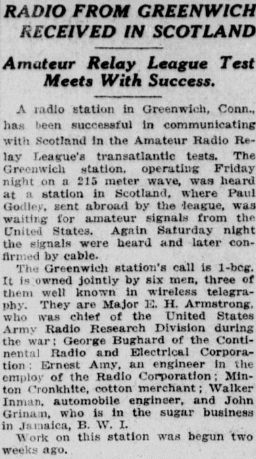

Numerous stations were heard the night of December 11, the most notable being 1BCG, as reported in the news clipping above. The signals from Connecticut were heard not only in Britain, but also on the Continent. A full message was picked up by Godley from the station at 3:00 AM GMT, or 10:00 PM in America.

Through special arrangements with the Marconi Company, word was sent back to America on the high powered commercial station MUU. Even though Marconi used automated high-speed code, it allowed this message to be sent by hand so that it could be copied by Amateurs in America directly. The message was acknowledged by Marconi’s American station, WII, also hand keyed for the occasion, to make sure that the word was heard throughout North America that the tests had been successful

Back in Hartford, ARRL officials were gathered around the longwave set tuned to MUU. According to the account in the February 1922 issue of QST, the air was so thick with tobacco smoke that it was hard to see how a signal could get into the room.

Today, communicating across the Atlantic is a pretty routine occurrence. We’ve learned over the years that even higher frequencies work even better than the ones used in 1921–most of which were in what we today consider part of the AM broadcast band. When I operate portable from a park using 5 watts, I made numerous contacts with Europe. It’s pretty easy now, and it’s something that’s been going on for a century now.

Various events will be taking place this weekend to commemorate the event. Most of these are listed at the ARRL website. In particular, I want to do my best to listen to a recreation of 1BCG’s transmitter, and you can read details of that event at this link.