Jules Andre Peugeot by French Army – Original publication: 1914, France. Immediate source: David O’Mara. Via Wikipedia

Jules Andre Peugeot was born at Etupes, France, on June 11, 1893. He was the son of Jules Albert Peugot and Francien Marie Frederique Pechin. He was a teacher, appointed to the school at Pissoux. He was regarded as a kindly man and well liked by his students. In 1913, he was conscripted into the French army.

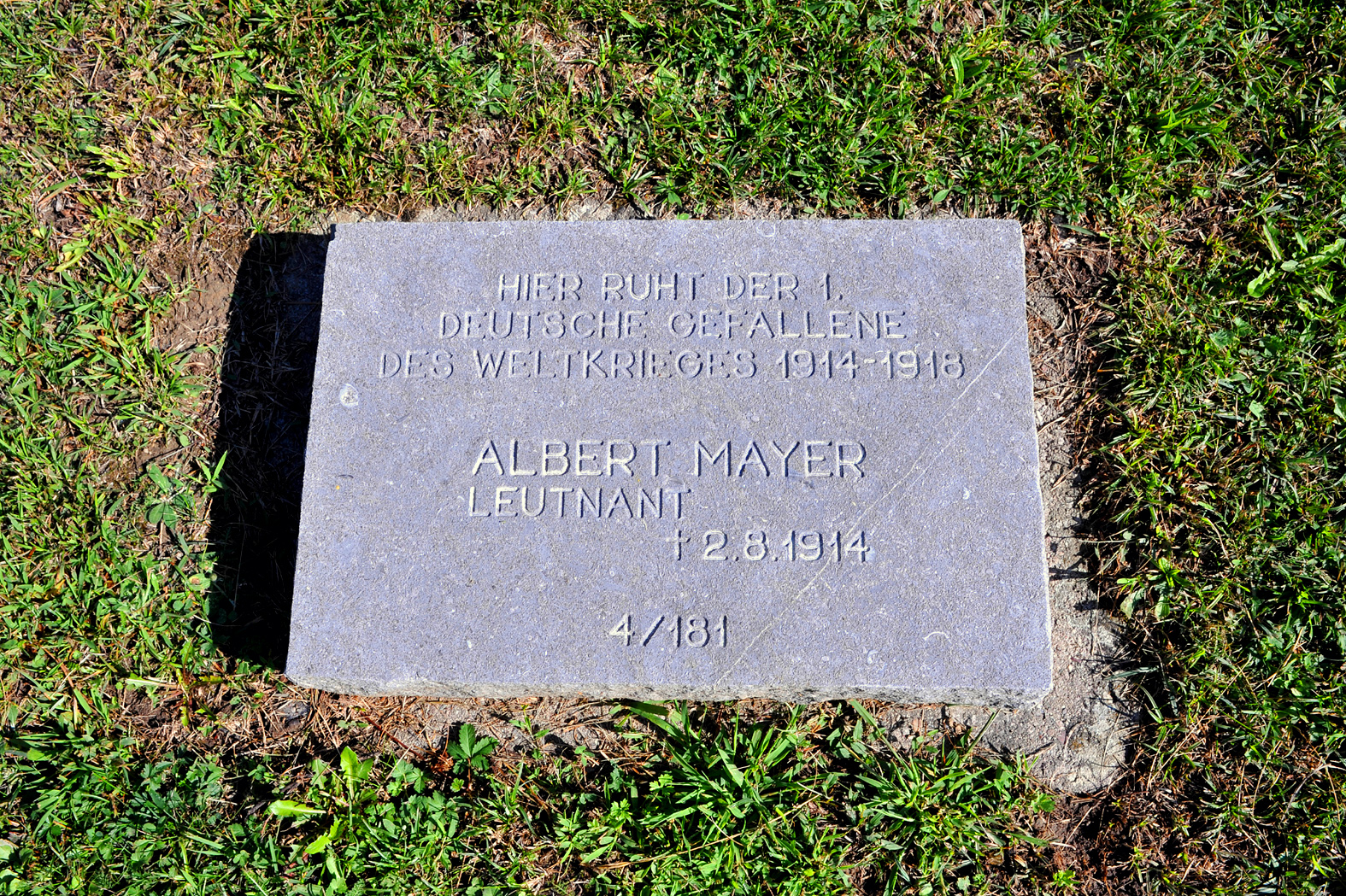

Albert Otto Walter Mayer was born on April 24, 1892, in Magdeburg, Germany. Shortly thereafter, his family moved to the Alsace region. He became a Lieutenant in the German army.

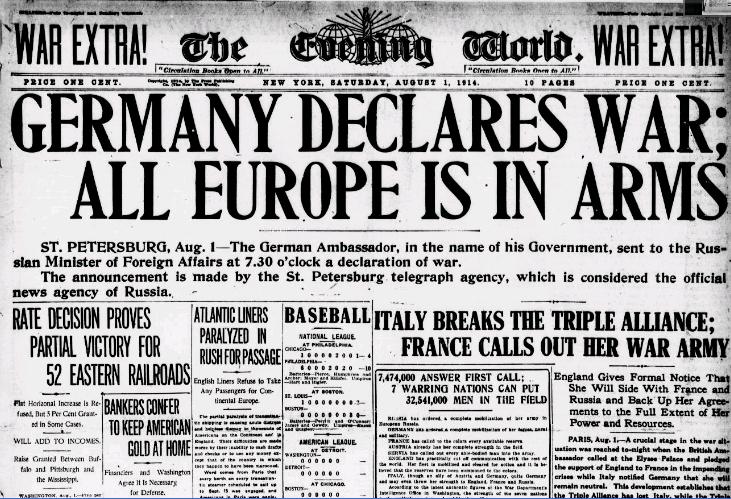

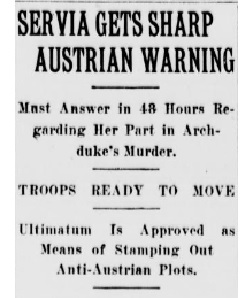

On August 2, 1914, the day before Germany officially declared war on France, Lt. Mayer was assigned to a reconnaissance squadron to sueveil French positions. At 10:00 AM, he approached the village of Joncherey.

Corporal Peugot had been having breakfast at the house of one Monsieur Doucourt, where he had been billeted. M. Doucourt’s daughter, Nicolet, came in and alerted the soldiers that a German patrol had entered the town. The soldiers ran out, and Peugot yelled at Mayer to stop. Mayer pulled out his pistol and shot Peugot. Peugot returned the shot but missed. The other French soldiers returned fire, however, killing Mayer. Peugot died a few minutes later on the steps of the house. The two bodies were placed side by side in the straw in a barn.

Mayer and Peugot were the first German and French casualties of the Great War.

Leutnant Albert Mayer Grabstein 01 09 par Хрюша — Travail personnel. Sous licence Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

In 2008, on the occasion of the death of the last French veteran of the war, French President Sarkozy remembered the two men:

The Frenchman was 21 years old. He was a teacher. His name was Jules-André Peugeot. The German is Alsatian, a native of the region of Mulhouse. He was just 20 years old. His name was (Albert) Camille Mayer.

They loved life as we love it in 20 years. They had no vengeance, they had no hate to satisfy.

They were 20 years old, the same dreams of love, the same ardor, the same courage.

They were 20 years old and felt that the world was theirs.

They were 20 years old; they believed in happiness.

They had barely left childhood and did not want to die. They both died on a beautiful summer morning, one with a bullet in the shoulder, the other shot in the stomach. They were the first unconscious actors in the same tragedy whose blind fate and folly had long secretly woven a sinister plot that would take its son in a sacrifice of heroic youth.

Both died at 20 years and did not see the terrible result of what they began: These millions of deaths, mowed down by machine guns embedded in the mud of the trenches, torn by shells. Nor did they see the huge crowd of millions of wounded, crippled, disfigured, gassed, who lived with the nightmare of war etched into their flesh.

They did not see their parents crying, widows mourning their husbands, children crying for their fathers. They did not experience the suffering of a soldier who smokes a cigarette to overcome the smell of dead abandoned by those who did not even had time to throw them a few clods of earth, so that do not see them rot. ”

These two young men of twenty years did not experience nights of rain, the winter in the trenches, “silent and shivering waiting long minutes like hours.” They did not cross columns returning fire “with their wounds, their blood, their mask of suffering” and their eyes seemed to say to those over, “Do not go there!” They did not fight tirelessly against mud, against rats, against lice, against the night, against the cold, against fear.

They did not have to live for years with the memory of so much pain, with the thought of so many lives Blasted next to them and the need to step over the body to mount an assault.

References

Rene Puaux, The Lie of the 3rd of August, 1914 (1917)

Jules-André Peugeot at Wikipedia

Jules-André Peugeot at French Wikipedia

Albert Mayer at French Wikipedia

The First to Fall: Peugot and Mayer

Skirmish at Joncherey at Wikipedia

Declaration of President Sarkozy (French)