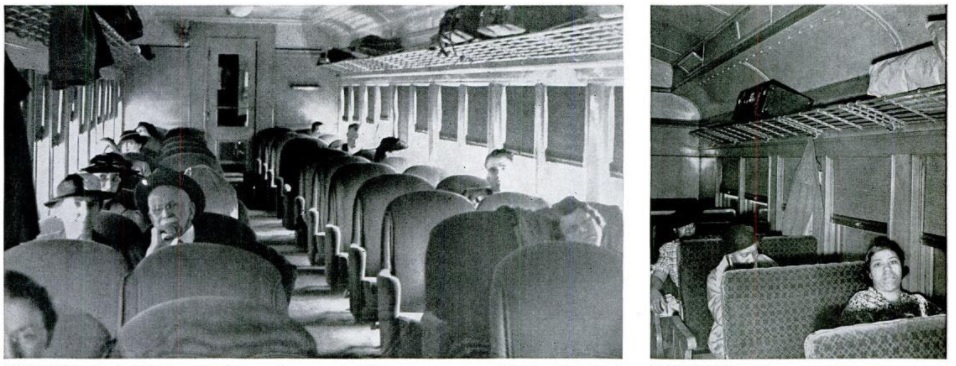

Eighty years ago today, Life Magazine, May 24, 1937, carried these images of two separate but “equal” rail cars in the southern United States. The car on the left was reserved for white passengers, with the one on the right for African Americans. The caption noted that the car for whites was spotlessly clean and air conditioned, with individual seats. For the same fare, black passengers travelled in a dirtier car without air conditioning with standard seats.

The magazine feature was prompted by a lawsuit by Rep. Arthur Mitlchel of Illinois, who was then the only black Member of Congress. In April, he had traveled by rail from Chicago to Hot Springs, Arkansas. He traveled in a Pullman car and first class coach until the train reached the Arkansas state line. At that time , as required by Arkansas law, the conductor asked him to move to the Jim Crow coach, which the Congressman called filthy.

He brought suit against the railroad, but made clear that he was not crusading for the end of Jim Crowism. Instead, he was seeking merely the “equal accommodations” promised by the law. He lost before the ICC and the District Court, but ultimately appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The case, Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 80 (1941) was decided in Mitchell’s favor on April 28, 1941. In 1896, the Court had ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), that “separate but equal” satisfied the Equal Protection clause. That case wasn’t overruled until 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). But in Mitchell, the Court held that equal does, indeed, mean equal.

The railroad and the ICC had argued that there was little demand for first class accommodations by African-American passengers. In fact, the evidence suggested that Mitchell was the first black person to request first class accommodations on the train. But the court held that this was irrelevant, since the ruling “made the constitutional right depend upon the number of persons who may be discriminated against, whereas the essence of that right is that it is a personal one.”

The practical difficulties were irrelevant, according to the court. It was enough that the discrimination had taken place.