Morse sending message from Capitol. Wikipedia image.

Today marks the 175th anniversary of the first use of the electric telegraph on May 24, 1844, a message sent between Washington and Baltimore by Samuel F.B. Morse.

Today marks the 175th anniversary of the first use of the electric telegraph on May 24, 1844, a message sent between Washington and Baltimore by Samuel F.B. Morse.

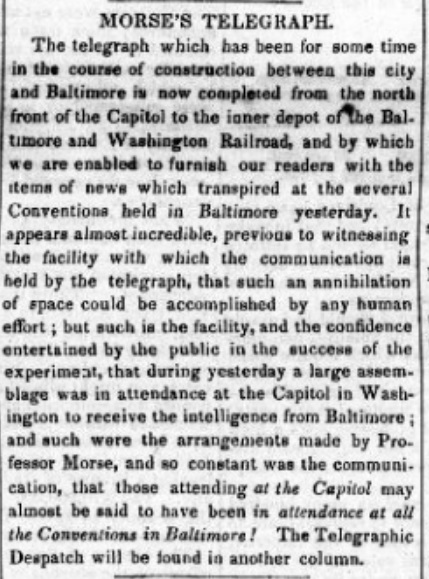

As shown by the newspaper clipping to the left, the device was in immediate commercial use. The article appeared in the Whig Standard on May 28, 1844.

The 38-mile line was authorized by Congress in 1843, and $30,000 was appropriated. It was completed by May 1, 1944, and a demonstration took place that day. This is the demonstration apparently being discussed in this article, since the May 1 demonstration included sending the news of the Whig Party’s nomination of Henry Clay for President. The author of that article announces in astonishment that “those attending at the Capitol may almost be said to have been in attendance at all the Conventions in Baltimore!”

Morse in 1857. Wikipedia photo.

The line officially opened on May 24, 1844, with Morse in the Capitol building sending the words “what hath God wrought” to Baltimore. Within the next six years, 12,000 miles of line were placed.

Interestingly, the word “telegraph” was already firmly ingrained in the English language. Morse’s invention might have been the first electric telegraph, but other devices for sending signals over a long distance already existed. For example, I have transcribed the 1797 Encylopaedia Britannica article on the telegraph, which describes some of the pre-electric telegraphs.

Most readers are undoubtedly aware of the current uses of Morse Code, even 175 years after its first use. An interesting article at Smithsonian.com explains some of them.

The International Morse Code is standardized by the International Telecommunications Union. The most recent addition to the code is the addition of the @ sign ( .– – .– .) in 2002.

Historical marker along path of Washington-Baltimore line. Wikipedia photo.