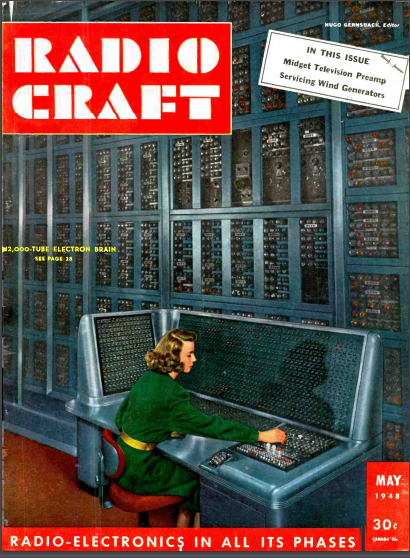

Seventy years ago this month, the cover of the May 1948 issue of Radio Craft showed the latest in electronic computing equipment, this 12,000 tube electronic brain, the IBM Selective Sequence Electronic Calculator.

Seventy years ago this month, the cover of the May 1948 issue of Radio Craft showed the latest in electronic computing equipment, this 12,000 tube electronic brain, the IBM Selective Sequence Electronic Calculator.

Along with those 12,000 tubes, the computer contained 21,400 relays and 40,000 pluggable connections. Power consumption was about 180 kilowatts, and the machine had an extensive fire suppression system built in. The accompanying article began with an example of computing the position of the moon, given a starting point of December 31, 1899. This task would take a human about three weeks, but the IBM was able to crank out the calculations in a mere seven minutes.

The computer covered the walls of a specially designed room measuring 40.6 by 86.6 by 14 feet. In a minute, it was capable of 3500 additions or subtractions of 19 digit numbers, 50 multiplications or 30 divisions of 14 digit numbers. Logarithms and trigonometric functions were stored on magnetic tape, and when one of these functions was required, the required value was looked up from the table prerecorded on the tape. Punched cards or magnetic tape were used for storage and input and output.

Memory during the arithmetic functions was handled by trigger circuits using ordinary 12SN7 dual triode tubes.

According to IBM President Thomas J. Watson, “this machine will assist the scientist in institutions of learning, in government, and in industry, to explore the consequences of man’s thought to the outermost reaches of time, space, and physical conditions.” But the machine “cannot, and never will, replace the human scientist as its purpose is only to follow his commands. If the incorrect instructions are given to it, it will follow them. The scientist is supreme over the great electronic calculator, which is his child to assist him in exploring the ever-profound depths of science.”