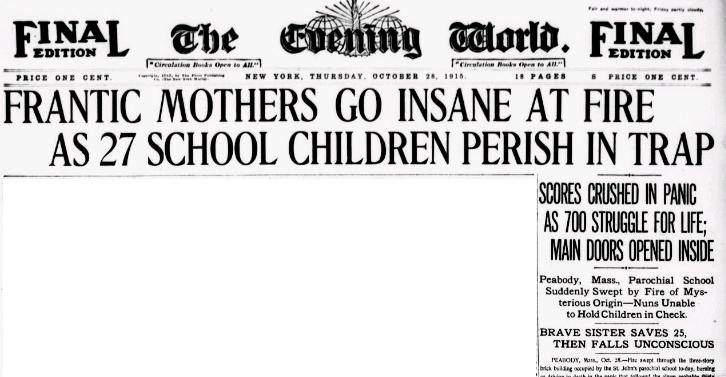

One hundred years ago today, twenty-one girls between the ages of 7 and 17 were killed in a fire at St. John’s School in Peabody, Massachusetts. Under the school’s established fire procedure, most students were to leave the building through a rear exit. But because the route was blocked by thick smoke, most instead tried to exit through the front door, where they became blocked in the vestibule. A major contributing factor was the fact that the front doors opened inward. The crowded vestibule was soon engulfed in flames, and the entire building was soon fully engulfed.

Most students were able to escape through first-floor windows, or even by jumping from higher windows. The school’s teachers, nuns of the Sisters of Notre Dame, acted heroically, by dropping many of the students to improvised life nets made of coats and blankets.

One lesson learned from this fire was that the exit doors of public buildings need to open out to avoid bottlenecks in case of fire. In the wake of the fire, Peabody became the first city to impose this requirement.

Every school with which I have been involved takes fire safety very seriously, and it is natural to ask the question of how successful these efforts have been. In other words, how often do we see a headline like the one at the top of this page?

The answer is that school fire safety has been extraordinarily successful. In the past half century, zero American schoolchildren have been killed by fires. There have, of course, been fires. But in over fifty years, there has not been a single fire fatality. Not a single one. And when we stop to think of why this is true, we can learn some lessons that will help prevent other tragedies.

The important thing to remember is that we cannot point to a single magic bullet that has prevented school fires. There is no one thing that we did to prevent them. We did a lot of things. And when we did them, we didn’t waste time worrying that we shouldn’t do them because that one thing wouldn’t prevent all fire fatalities. Nobody would call us paranoid for taking all of those precautions against something that hasn’t happened in 50 years. And nobody would argue that we shouldn’t take fire precautions because they might scare the children.

In the St. John’s fire, the critical lesson learned was that doors to public buildings should open out. But no sane person would stop there and conclude that by changing the doors on the school that we could prevent fire deaths. We fixed one safety hazard, but continued identifying other hazards. Here are some of the other things we have done for school fire safety over the years:

- We use fire-resistant building materials.

- Students and staff have routine fire drills.

- Firefighters are familiar with the layout of the schools in their area.

- Exits are well marked and the exit signs have backup power.

- Adequate fire hydrants are in place near schools.

- The locations of fire stations take into account proximity to schools.

- Fire extinguishers and fire alarms are required.

- Most schools are equipped with sprinklers.

There are probably others that I’ve forgotten. But you get the idea. We haven’t had any fire fatalities because we have multiple redundant layers of protection. And nobody says that doing all of these things makes us paranoid. We’ve had zero fatalities because we do them.

During the same half century of extraordinary success in school fire safety, there have been more than 300 deaths from school shootings. Security expert Lt. Col. Dave Grossman makes the compelling case that we have to stop being in denial about school violence. Invariably, in the wake of a school shooting, the inclination is to come up with a single solution that will prevent the next one. But we need to take the same approach that we do to fire safety: What we really need are multiple redundant layers of protection. Some of the possibilities suggested by Grossman include:

- Have an (armed) police officer in the school.

- Have a single point of entry to the building and classrooms.

- Have regular drills

- Allow police officers to carry weapons off duty. Grossman points out that nobody considers it paranoid for an off-duty firefighter to have a fire extinguisher in the trunk of the car when dropping his or her kids off at school. And it would be no more paranoid for a parent who was a police officer to be prepared.

- Equip all patrol officers with rifles and smoke grenades.

- Be prepared to use fire hoses to deal with active shooters.

- Finally, Grossman points out that “armed citizens can help.”

Will any one of these steps prevent every possible school shooting scenario? No. Having a police officer in the school is not the one magic bullet that will prevent every school shooting. Having the responding officer equipped with a rifle in his or her trunk is not the one magic bullet that will prevent every school shooting. And having a handful of random citizens armed is not the one magic bullet that will prevent every school shooting.

But having sprinklers is not the one magic bullet that will prevent every fire death. Having fire drills is not the one magic bullet that will prevent every fire death. Having doors that open out is not the one magic bullet that will prevent every fire death. But we did all of those things anyway, because if we do all or most of these things, then it is very likely that these multiple redundant precautions together will prevent most fire deaths. The last half century of American history proves that this is true.

A hundred years ago, when 21 girls were killed in a school fire, we learned one lesson, but we also kept on learning our lessons. Lessons were learned from the fire at Our Lady of the Angels School in Chicago on December 1, 1958 when 95 were killed. The net result is that we have learned these lessons, and we continue to have multiple redundant layers of security to prevent them. And because those measures have proven so successful, we keep at it. Nobody says that we’re paranoid. Nobody tells us to stop because we’ll scare the children. We simply do what we need to do because it works.

According to findagrave.com, these are the names of the girls killed in the fire a hundred years ago today:

- Agnes Ahearn

- Mabel Theresa Beauchamp

- Helen Theresa Bresnahan

- Florence Burke

- Nellie Elizabeth Carty-Burns

- Patroni Chebator

- Elizabeth Comeau

- Catherine M. Compiano

- Ann Daleski

- Florence Doherty

- Mary Ida Essaimbre

- Mildred Fay

- Marion Hayes

- Annie Jones

- Helen Keefe

- Annie L. Kenney

- Mary Elizabeth McCarthy

- Mary Meade

- Elizabeth Nolan

- Annie E. O’Brien

- Catherine M. O’Connell

At that same site, you can view the statue erected in 2005 in memory of the girls who were killed. It depicts two of them in the embrace of their Saviour.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()