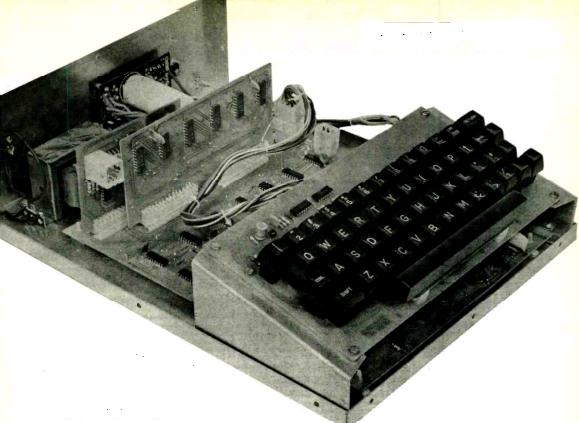

40 years ago, careful observers were probably anticipated that something like the Internet would sometime come to pass. For those early adopters, Radio-Electronics magazine carried plans for a terminal, which the magazine called the TV Typewriter II, since an earlier version had appeared in the magazine in 1973. Some of the chips used in the 1973 design, however, turned out to be unobtainium, and the 1974 model featured use of commercially available 74-series TTL chips. The plans included a keyboard (hence “typewriter”), and called for connection to a black and white TV for the display (hence “TV-typewriter”). The plans for the 1974 model, shown here, are found in the February, March, and April, 1975, issues of the magazine.

The terminal had an RS-232 interface, and could communicate at 110, 220, 440, or 880 baud, or if a different crystal was used, 150, 300, 600, or 1200 baud. The terminal had two potential applications. First, the article noted, would be “data communications with computers. Combined with a keyboard, we have one of the fastest and most efficient means for an individual to communicate with a machine.” One example of a computer with which it could communicate would be the fledgling home computer described in the magazine’s July, 1974, issue.

Another, possibly more common, use for the TV-typewriter was also given: “Of course, if you don’t have or don’t want your own machine, you can always tie into a full size time-shared system, assuming you have access to one.”

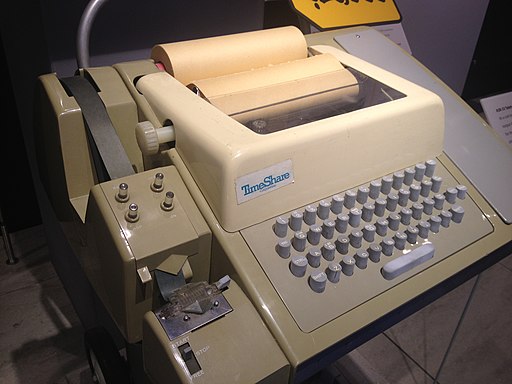

This statement shows how the TV-typewriter foreshadowed the Internet. My first experience with computing involved one of those time-shared systems. In my case, I accessed the Minneapolis Public Schools’ timesharing system with the use of a 110-baud teletype machine, like the one shown here. To use this terminal, we dialed the phone number of the timeshare system computer, placed the telephone receiver into the acoustic coupler modem, and after logging in we were able to do things such as write short basic programs. Later on, other systems such as the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium‘s MECC-MERITTS system, which also included a rudimentary chat function.

Of course, accessing such a system required having physical access to a terminal, which nobody other than the school owned in those days. Something like the TV-Typewriter would have been an incredible luxury for those of us interested in the proto-internet offered by the timesharing systems.

Many of us back in those days figured out that it was just a matter of time before something like the Internet came into being. However, most of us were wrong in one regard. We believed that online computing would follow the model of those timeshare systems: There would be a big computer somewhere doing all of the computing, and users would access it using a dumb terminal like a teletype machine or the TV-Typewriter.

In some respects, our predictions were borne out a few years later when CompuServe came along in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s. It was way out of my price range, at about $5 per hour (a rate at which it would cost about $20 to download the entire contents of a daily newspaper). But since I worked for Radio Shack, which was one of its primary sellers, I did have limited access and was able to use it to read the handful of newspapers online, get aviation weather, and even access the early chat server. There was even something called “Email,” a registered trademark of CompuServe. It was still out of my price range, and I never even sold a single subscription, but I realized that it was the future of computing.

Except I was still wrong on one detail. I still assumed that online content would be delivered the way that CompuServe was doing it: Individual users would use a dumb terminal to call a big computer somewhere that delivered the content. The 1981 video below is a newscast about the early days of CompuServe. It also makes clear that this is the model: Once a day, the newspaper in San Francisco programs into a computer in Columbus, Ohio, the contents of the daily paper.

Most of us believed that was how it would work, and we were wrong. We probably could have figured this out, because to access that computer in Columbus Ohio, we weren’t exactly using a dumb terminal. We were using a computer (at that point, the TRS-80 Model 100). By today’s standards, the computer didn’t have much computing power. It had 8 kB memory and ran at 2.4 MHz. But that computing power was doing only one thing: Emulating a dumb terminal. The computing power wasn’t being used, other than to duplicate the functions of the 1975 TV-Typewriter.

By the early 1980’s, the first computer bulletin board systems (BBS’s) were starting to appear. They esentailly followed the same model as the early timesharing systems and CompuServe. The only difference was that they were much smaller systems, generally run by hobbyists. But the end user still called up the “big computer” with a dumb terminal. The real origin of the internet is best seen in a development that took place a few years later, when BBS systems began to be linked up as FidoNet. FidoNet was developed starting in 1984. Users would still call in to a single local BBS. But at night, when the phone rates were low, those BBS’s would communicate with one another and transfer mail, discussion posts, and files. While the end user would still interface only with one local “big” computer, the information he or she was reading actually originated on some other computer. In other words, the information was no longer centralized in Columbus, Ohio. The absence of one computer from the larger network would hardly be noticed. For home users, the Internet really began in 1984 when FidoNet allowed them to access information globally from a dumb terminal. Most users of these BBS systems were using computers with some computing ability. I doubt if too many TV-Typewriters were being used in 1984. But the TV-Typewriter, assuming that someone got one working in 1975, would have been perfectly adequate to the task.

The TV-Typewriter by itself was still missing one important component. It did not include the modem. To use it with a timesharing system (or a few years later, with CompuServe or FidoNet), the builder would also need to construct a modem to get those 110 baud signals into the phone line.

For those who built the TV-Typewriter, they probably had some inkling that there would be an Internet someday. They had the details wrong. They probably thought that there would be a big computer in Columbus Ohio to which they would connect. But they probably had some of the basic ideas.