The drafters of this document also had problems deciding who got to run the meeting. But even the Democrats of 1857 agreed that no member of the state shall be disfranchised unless by the law of the land or the judgment of his peers.

According to the Star Tribune, mayhem broke out tonight at a DFL precinct caucus in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood of Minneapolis. 300 people were present, most of them Somali Americans. An altercation took place about who would chair the meeting. Cops were called, and both the fight and the caucus were broken up less than an hour after they started. No business was transacted, police escorted attendees out of the building, but no arrests were made.

Republicans probably would have resorted to the simple expedient of having a vote, and letting a majority of those present decide who should chair the meeting. (Although Republicans also sometimes resort to calling the cops, seizing microphones, and other similar measures when a majority gets in the way of someone’s carefully made plans, as evidenced by the 2012 state Republican conventions in

Louisiana, Oklahoma, and other states.)

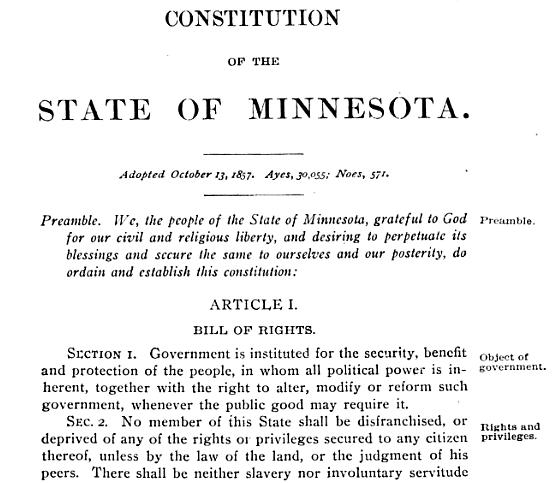

But having two people trying to chair the same meeting is nothing new to Minnesota politics. Indeed, Minnesota is unique in the Union in that it has two constitutions, based upon an incident not unlike that which occurred Tuesday night in Minneapolis.

When the Minnesota Constitutional Convention convened in 1857, there were two men on the platform purporting to chair the meeting. The Democratic chairman took a motion to adjourn until the next day. Meanwhile, the Republican chairman continued to preside, and the Republicans got down to work. The Democrats then left the chamber for the day.

Upon their return the next day, the Democrats found the chamber occupied. Undaunted, they simply moved down the hall to the other chamber, and held their own convention. Each convention published its own journal of the proceedings.

Somehow, a small conference committee was able to produce a single document to which both sides could agree. However, the two conventions never met together, and two copies of the document were ratified, one subscribed by the republican delegates, and the other subscribed by the democratic delegates. One of these copies was officially transmitted to Congress. However, the other copy found its way to Washington as well, and it was this second copy that was attached to the bill admitting Minnesota to the Union. Therefore, both versions, with their minor differences, stand on equal footing. When the placement of a comma is critical to the interpretation, lawyers still need to look at the two original handwritten documents and see whether the comma is really there in both copies.

So two people trying to run the same meeting is nothing new. But the Republicans generally do a better job of sorting out such messes, and even the Democrats of 1857 performed admirably at solving this little problem.

If you happen to find yourself disfranchised by your party, especially if you find yourself disfranchised because you’re a new American, perhaps you should think of finding a party that doesn’t have such a history of disfranchising people.