Today, if you want to contact someone who is traveling, it’s a simple matter of dialing their cell phone number. Wherever they are in the country, or even the world, their phone will ring, and you will be speaking with them. You can text that same number, or e-mail them, and you can be reasonably certain that you will contact them. And you don’t need to know where they are.

This is a new phenomenon, and it hasn’t always been this way. As recently as 30 years ago, if you wanted to contact someone, then you needed to know where they were.

Things began to change with the advent of cellular phones in the early 1990s, but only if the person had a cellular phone, which wasn’t always the case. And you had to know their phone number. For many users, the number was a closely guarded secret. They had to pay per minute for all calls–incoming and outgoing–so they didn’t give the number to just anyone. (Some countries solved this problem by having callers pay, but in the United States, almost without exception, the cellular subscriber had to pay for the airtime.)

But at first, even if you had the number, there was no way to call someone outside of their home area, without knowing where they were. In short, if you were on the road, you might be able to make outgoing calls, but you wouldn’t be able to receive incoming calls.

This 1990 news article made a prediction, which seemed almost unbelievable at the time:

Currently, callers seeking someone who has traveled away from his or her local calling area must know where that person is in order to complete a call. With automatic call delivery, a person “roaming” outside the home market will send out a locating signal to the closest cellular system whenever he or she turns on the cellular phone. Computers then will do the searching and service authorizations.

“If you’re up in Chicago and I’m back in Washington and all I’ve got is your local Washington number, I’m going to be able to dial that Washington number . . . and that phone call is going to find you . . . anywhere in the United States,” said Norman Black, a spokesman for the cellular phone association.

That was almost unbelievable, but according to the article, it was going to happen by 1992. It did eventually happen, but for most customers, it took a bit longer.

Prior to the 1990s, there was really no way to contact someone who was traveling, unless they called you. In emergency situations, broadcast stations might fill in. Occasionally, on stations such as WCCO Minneapolis, it wasn’t uncommon to hear a message such as the following:

The Minnesota Highway Patrol has asked our assistance in locating John Doe of Minneapolis for an emergency message. John Doe of Minneapolis, please call the Minnesota Highway Patrol for an emergency message.

When I heard those, I always wondered what kind of tragedy befell that particular family. But presumably, they heard their name on the radio, called the Highway Patrol, and were put in touch with whoever had the bad news for them.

In 1973, an idea came along that was ahead of its time–a method to contact travelers anywhere in the country. Messages could be sent to anyone anywhere in the country, as long as the traveler was willing to stop at a popular roadside retailer. It was really an early version of e-mail, and certainly one of the first methods of digital communication that most Americans had ever seen.

The retailer was Stuckey’s, and the system they pioneered was called “Highway Emergency Locating Paging Service“, or HELPS for short. The chain had 350 stores nationwide, all strategically located along major highways. They had clean restrooms, they sold snacks, and most had gas pumps. It was the kind of place where you had to stop anyway, and the idea was that if you could also use their stores to keep in touch with family or business associates back home, then it would be a competitive advantage for them.

The retailer was Stuckey’s, and the system they pioneered was called “Highway Emergency Locating Paging Service“, or HELPS for short. The chain had 350 stores nationwide, all strategically located along major highways. They had clean restrooms, they sold snacks, and most had gas pumps. It was the kind of place where you had to stop anyway, and the idea was that if you could also use their stores to keep in touch with family or business associates back home, then it would be a competitive advantage for them.

The store was equipped with a computer console with a CRT screen and 10 digit numeric keyboard. Before you left on your trip, you would tell the folks back home that they could always reach you by calling the Stuckey’s HELPS line in Georgia. From early in the morning to late at night, a friendly operator would answer the phone. After hours, there was answering machine. The caller would tell the operator that they had a message for you, and give the operator your home phone number (or other agreed-upon number). The message would be a phone number that you were to call back.

When you stopped for gas at any of the 350 Stuckey’s locations, you would go inside and use the free terminal. It would prompt you to enter your phone number. The terminal would link back to Stuckey’s headquarters via Western Union lines, and would display any messages, or tell you that you had none. If you had a message, then you would go to the payphone and call them. You would have to pay for a long distance call, but you only had to pay for one long distance call.

The beauty of this system was that the caller didn’t need to know where you were. As long as you bought your gas at Stuckey’s, it didn’t matter if you were in Maine or California–you would get the message.

The system got the approval of the New York Times:

Stuckey’s deserves a large bouquet of pralines and a rousing round of applause from the motoring public for having invented a free, public service with no strings attached that is probably the greatest contribution to the motorist’s peace of mind since the free gas company roadmap and the hopefully clean gas station rest room.

The console had a second function. The store manager had a key that converted it into a terminal for ordering stock from the company’s warehouse. The annual cost of the system was estimated at $660,000.

As a youngster, I remember seeing one of these machines and thinking to myself what a good idea it was. Of course, I entered our home phone number, and there were no messages for us. As far as I know, it didn’t last long, and I never saw another one of the terminals. It was a very good idea, but perhaps a bit ahead of its time.

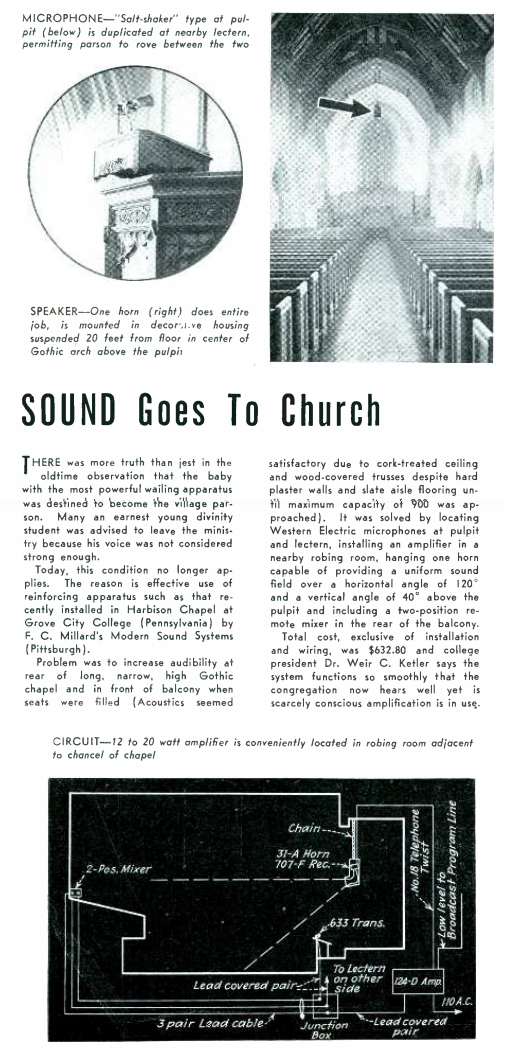

There was a time, not so long ago, when an absolutely necessary skill for any kind of orator was the ability to project one’s voice. Entire books were written on the subject, such as this one that notes:

There was a time, not so long ago, when an absolutely necessary skill for any kind of orator was the ability to project one’s voice. Entire books were written on the subject, such as this one that notes: