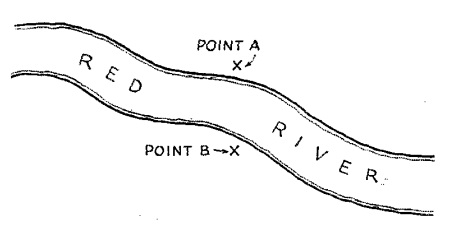

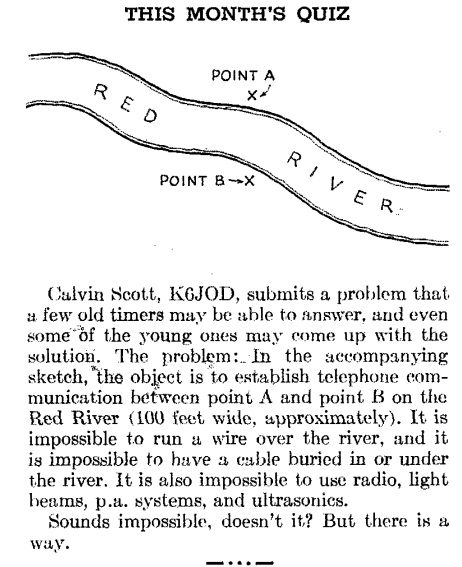

Yesterday, we presented the problem of how to hook up a telephone to talk across a river from Point A to Point B, without running a wire across the river.

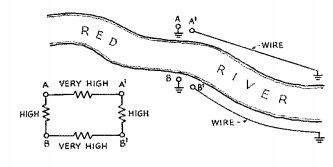

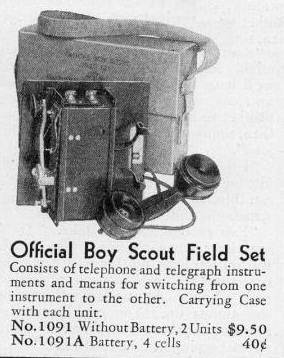

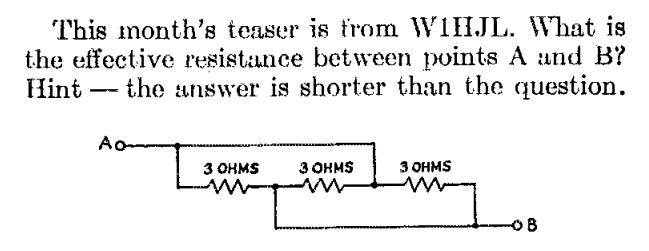

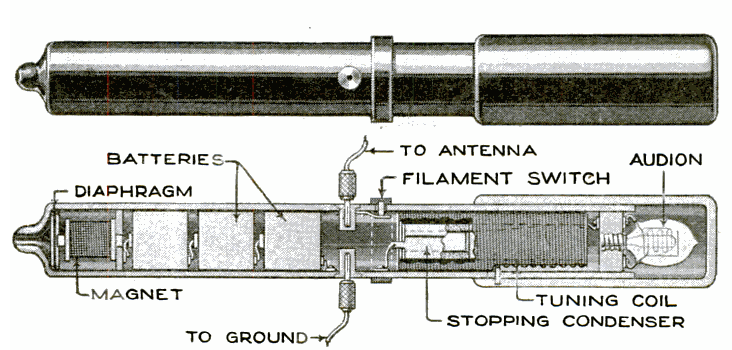

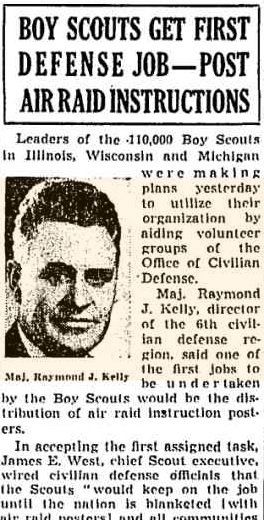

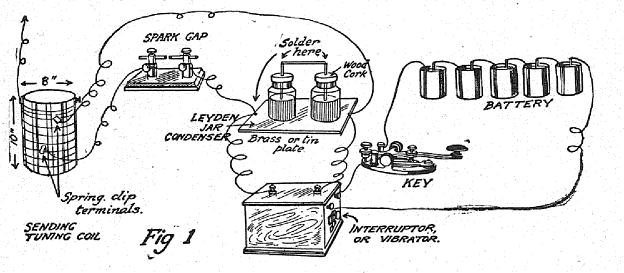

Loyal readers knew the answer right away, because we presented a similar system for a 1940 wireless telegraph using four ground rods. Each side of the circuit was connected to two ground rods. The January 1957 issue of QST shows a similar arrangement for how the two Boy Scouts could hook up their field telephone:

Each telephone is hooked up to two ground rods. The magazine suggests separating them by 20 times the width of the river (2000 feet). There’s still a high resistance path between the two telephones, but the leakage resistance between A and A’ and between B and B’ is even higher. The 1940 wireless telegraph, because it used an audio amplifier, could probably get by with less separation between the ground rods on each side of the river. But with 2000 feet separation, the scouts’ telephones should work just fine, despite not being able to run any wire across the river.