Many Point Scout Camp is owned and operated by the Northern Star Council of the Boy Scouts of America, and has been in operation since 1947. Local scouts and scouters don’t always realize what a gem it is, and those in other parts of the country are often unable to comprehend its sheer size. It covers 2400 acres and nine miles of shoreline on two lakes, Many Point and Round Lake. At 15 miles per hour, it’s about a 30 minute drive from one end of the camp to the other, and it’s another 30 minute drive to the nearest full-service gas station or supermarket. Therefore, it provides a real wilderness experience to thousands of scouts.

Because of its size, it lies on land that has seen its share of history, and since 1996, it has included a very nice History Center to showcase some of that history. In addition to the scouting that’s taken place there since 1947, the museum contains displays regarding the earlier users of the land. Therefore, it has displays about the Native Americans, the fur traders, the loggers, and the sportsmen. In the first half of the 20th century, several resorts were located on the land where Many Point is now located, and one of these is recreated in the museum. (A complete guide to the History Center is available online.)

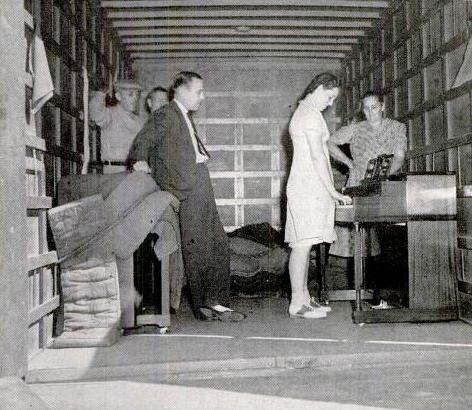

What caught my eye, of course, was the Philco portable radio shown here. The set, it turns out, is a Philco model 41-841, which would have been manufactured shortly before the War in 1941. So as far as the age of the set, it’s consistent with the display.

What caught my eye, of course, was the Philco portable radio shown here. The set, it turns out, is a Philco model 41-841, which would have been manufactured shortly before the War in 1941. So as far as the age of the set, it’s consistent with the display.

It is a battery-operated portable, which ran off a 3 volt A battery for the filaments, and a 90 volt B battery. It was also capable of running off household current, using a 117Z6G rectifier for the B+. When run on household current, the filament voltage was provided by simply dropping the rectified power supply through two resistors. The set’s schematic can be found at this link, and you can read more discussion at this link and this link.

In addition to the rectifier, the set has four tubes, a 1A7G, 1N5G, 1H5G or 1LD5, and 3Q5G. It’s a fairly typical superheterodyne, and has provisions for external antenna and ground. At night, the fishermen sitting around the table would be able to hear scores of stations from the Twin Cities, Chicago, and around the country. One of the strongest stations at night probably would have been WDGY, whose nine-tower array cast a formidable signal to the north.

During the daylight hours, the set would probably get a fairly good signal from WDAY in Fargo, North Dakota. In addition, it might possibly have pulled in 50,000 watt WCCO or then 25,000 watt KSTP in the Twin Cities during the daylight hours.

Seventy-five years ago, this unnamed California Boy Scout decided to bring his radio to camp. The set was one he built himself in a cigar box. The caption in this picture from the August 1940 issue of Boys’ Life reveals that the picture was taken at the Camporee of the BSA’s Oakland Area Council.

Seventy-five years ago, this unnamed California Boy Scout decided to bring his radio to camp. The set was one he built himself in a cigar box. The caption in this picture from the August 1940 issue of Boys’ Life reveals that the picture was taken at the Camporee of the BSA’s Oakland Area Council.![]()

![EF50 tube, Wikipedia photo. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EF50.jpg By RJB1 (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://onetuberadio.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/180px-EF50.jpg)