I’ve shared previously about my deprived childhood. We didn’t have a color TV. We didn’t have a real fireplace–we had a carboard fireplace. I didn’t have a TV in my room. We didn’t even own a robot, which I was convinced that most more affluent families owned. Yes, it was horrible.

I’ve shared previously about my deprived childhood. We didn’t have a color TV. We didn’t have a real fireplace–we had a carboard fireplace. I didn’t have a TV in my room. We didn’t even own a robot, which I was convinced that most more affluent families owned. Yes, it was horrible.

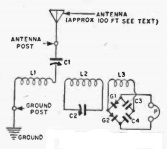

But before you express too much sympathy, I guess I had better ‘fess up. We had a built-in TV. That’s right, down in the basement rec room, we had a TV that was permanently built in to the wall. As far as I know, it came with the house. In a small locked room, which we called “the TV room,” for want of a better name, the chasis of the set was there in all of its glory, with a piece of twin-lead cut as an antenna.

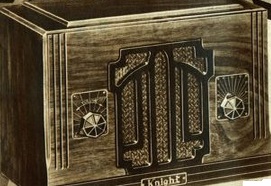

I remember that the set was an Admiral, and I’ve been able to figure out that it was a 1958 model, designed to be built in. The set tuned VHF only, meaning that it couldn’t be used to watch the fleeting signals of our only UHF station, channel 17.

I was able to find out some information thanks to the apparent practice of the Miami News to simply run a company’s press release as news. The August 4, 1957, edition of that paper carries a story under the headline “Built-In TV Announced By Admiral,” which almost certainly describes the model that was embedded in our wall. The article/press release enthusiastically reports that Admiral’s television sales manager, Ross D. Siragusa, Jr., had just announced the set’s 110-degree angle picture tube, along with the slim chassis depth of only 16 inches, made it the first nationally advertised set suitable for built-in applications or custom cabinetry.

The article identifies our set as being Admiral model B121F1, and that it included the “Imperial 440 chassis.” I found the image of this set, identical to the one in our basement, in a furniture catalog, apparently from 1958.

Our TV even made Life Magazine. The April 7, 1958, issue carries an Admiral advertisement masquerading as an article, given away by the tiny word “ADVERTISEMENT” at the beginning. (We see that Admiral was able to quite successfully push the envelope when it came to publicity.) The “article” recounts the experiences of an Elgin, Illinois, milkman who found himself inspired by visiting the modern kitchens of the well-to-do residents of Elgin. He was very impressed by the built-in appliances in their homes. He came to the realization that he could duplicate the effect in his own kitchen on a milkman’s salary by using free-standing Admiral appliances with the “built-in look.”

Our TV even made Life Magazine. The April 7, 1958, issue carries an Admiral advertisement masquerading as an article, given away by the tiny word “ADVERTISEMENT” at the beginning. (We see that Admiral was able to quite successfully push the envelope when it came to publicity.) The “article” recounts the experiences of an Elgin, Illinois, milkman who found himself inspired by visiting the modern kitchens of the well-to-do residents of Elgin. He was very impressed by the built-in appliances in their homes. He came to the realization that he could duplicate the effect in his own kitchen on a milkman’s salary by using free-standing Admiral appliances with the “built-in look.”

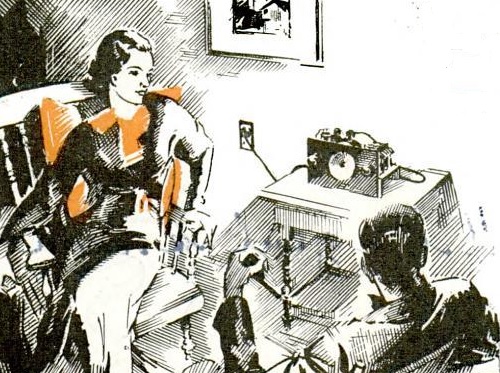

In the picture shown here, we can see him being inspired in one of those upper-class kitchens. And sure enough, one of the luxuries enjoyed by those high-class Elgin residents was a built-in Admiral TV. They were so rich that they were able to incongruously put the $239 21-inch TV right in the kitchen.

Both renditions had the dual speakers mounted in a grill right above the set, just like ours.

Those of us who weren’t quite so well to do didn’t have a TV in the kitchen, much less a gigantic 21-inch model. We had to settle for having it in the basement, and we couldn’t even get the elusive Channel 17. But that stands to reason, since we didn’t even have our own robot like those rich folks in Elgin probably did.

Our built-in B121F1 appears to be identical to the T21E21 which came with cabinet. It also appears to be identical with the console shown in this ad.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()