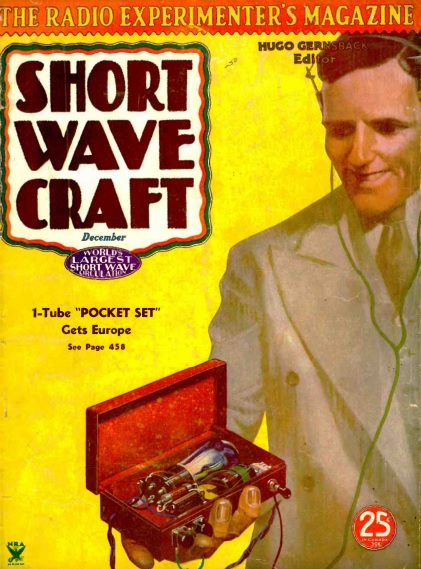

80 Years ago, the cover of the December, 1934, issue of Short Wave Craft featured this pocket portable one-tube superregenerative receiver covering the 49 meter shortwave broadcast band. According to the article, the receiver was able to pull in Europe without an antenna. And when tested with a short antenna in the magazine’s offices in a steel frame building in New York, the set picked up “stations galore.” The article notes that the receiver’s superregenerative circuit had one serious drawback: It radiates a very strong signal. The article therefore recommended that “it be operated only in the less congested areas where there are few short-wave receivers and where the danger of interfering with others is nil.” In other words, this particular circuit probably wouldn’t pass muster under Part 15 of the current FCC rules as an incidental radiator.

The author of the article is George W. Shuart, W2AMN, later W4AMN. He also wrote several articles for QST in the late 1930’s through the 1960’s. His last contribution to QST appears to be a “Hints and Kinks” item in August 1978 for a CW filter. A 1946 QST article includes a biography which notes that Shuart had been licensed since 1928, and had written numerous articles for beginners, a result of which was that many amateurs got their start from his articles. It also revealed that Shuart was employed by Hammarlund as its Advertising and Sales Promotion Manager. He was the author of the 1937 Radio Amateur Course

published by the same magazine in which appeared this one-tube radio.

The 1934 article provides two possible solutions for carrying the batteries for this pocket radio. The filaments run on two penlight cells, and the B battery can be as low as 22-1/2 volts. One solution is to make the B battery out of penlight cells bundled together and carried in a pocket. The other alternative is to mount them on a strap “which forms a belt that can be worn around the waist. This is an old stunt used in stage tricks.” A picture of this arrangement is shown in the article, and I would advise against wearing this type of battery while visiting an airport.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()